Professional Curiosity

Amendment

In February 2026, this new chapter was added to the Universal Procedures section.

Professional curiosity is fundamental in social care practice and is often linked to safeguarding. However, it should form part of everyday practice to enable better understanding of people's lives and their situations. Professional curiosity is the capacity and communication skill to explore and understand what is happening within a family or person's life rather than making assumptions or accepting things at face value.

Professional curiosity can require practitioners to think 'outside the box', beyond their usual professional role, and consider people and families' circumstances holistically.

Curious professionals engage with people and families through visits, conversations, observations and asking relevant questions to gather historical and current information.

Professional curiosity means looking beyond the obvious and asking questions to fully understand a person's situation.

Examples include:

1. Exploring living conditions

- Noticing unopened letters or lack of food during a home visit and asking about financial or physical challenges.

2. Questioning assumptions about capacity or choice

- If an older adult repeatedly declines services, exploring whether this is due to emotional associations, or not fully understanding available options.

3. Observing subtle changes

- Picking up on signs of neglect, such as weight loss, and asking open questions rather than assuming the reasons behind this.

4. Checking for hidden carers or support networks

- Asking who helps with daily tasks rather than assuming the person lives alone without support.

5. Following up on inconsistencies

- If a person says they are eating well but the fridge is empty, gently probing to understand barriers like finances or access.

A practitioner visits Mr. A, a 78-year-old man referred for possible self-neglect. He insists he is "fine" and doesn't need help. The practitioner notices the home is cold, there's little food, and unopened letters are piled up.

Professional Curiosity Actions:

- Open-ended questions: Instead of accepting "I'm fine," the practitioner asks about Mr. A's daily routine to better understand what this looks like which also gives the practitioner the ability to probe further into specifics if required;

- Strengths-based approach: The practitioner acknowledges Mr. A's independence and resilience, asking what matters most to him (he values staying in his own home and gardening);

- Explores barriers: Learns Mr. A's heating was disconnected due to unpaid bills, and he cannot always get to the shops because of his physical health;

- Builds on strengths: Connects Mr. A with a local gardening club for social contact and arranges a volunteer shopper, while helping him access a fuel grant.

Outcome:

- Mr. A remains in his home, and feels respected and supported;

- His physical health improves with regular meals and warmth;

- He regains confidence and social connection through the gardening club.

There are multiple barriers to professional curiosity that can make it difficult to apply in practice. These barriers can come from organisational, systemic or personal factors preventing practitioners from fully understanding a situation. Below are some key barriers to be aware of:

- Time restraints;

- Adopting a ‘deal with and manage’, rather than an ‘explore and understand’ approach;

- Avoidance of difficult conversations due to fear of causing upset or conflict;

- Fear of asking sensitive questions due to concerns about being perceived as intrusive, overbearing or discriminatory in regard to a protected characteristic;

- Normalisation: becoming accustomed to certain ideas, actions, or situations, causing them to be taken for granted and no longer questioned;

- Confirmation bias: looking for evidence and information which supports or confirms your pre-held views, filtering out useful facts and opinions;

- Unconscious bias: unknowingly making decisions or judgements based on assumptions, personal beliefs, background, experiences, culture; and

- Virtual settings: information gathered from observations is reduced by contact being made over the phone or online.

The Think Whole Family agenda focuses on the importance of understanding a whole situation, who is involved and what this looks like, not just one person. This enables building on the family's strengths, as well as identifying areas of need that may be affecting the family.

The following are some key points to consider:

- Is there an understanding of who is in the family and the family dynamics, including barriers and strengths?

- Who else is involved with the family, for example friends, extended family, important social contacts such as places of worship, clubs, etc?

- Are there other agencies involved, such as Alzheimer's Society, memory clinic or Occupational Therapy who can provide valuable information?

- Is there recognition of the ability to cope? Consider what you can see as well as what you are told;

- Is there an open and honest relationship with the family, where concerns are explained and addressed and sensitive questions can be asked?

- Is there a clear understanding of what the person/family want and have these been explored with open discussions in terms of what resources are available?

- Be aware of assumptions, your own and others. Be prepared to challenge and be challenged;

- Has there been time for reflection with peers and supervision to explore and challenge possible assumptions?

- Has this information been verified with others?

Note: If working with people who may not have family members around them, the above approach is still relevant to others who they may deem as important, such as friends, neighbours and others linked to aspects of their identity e.g. church connections.

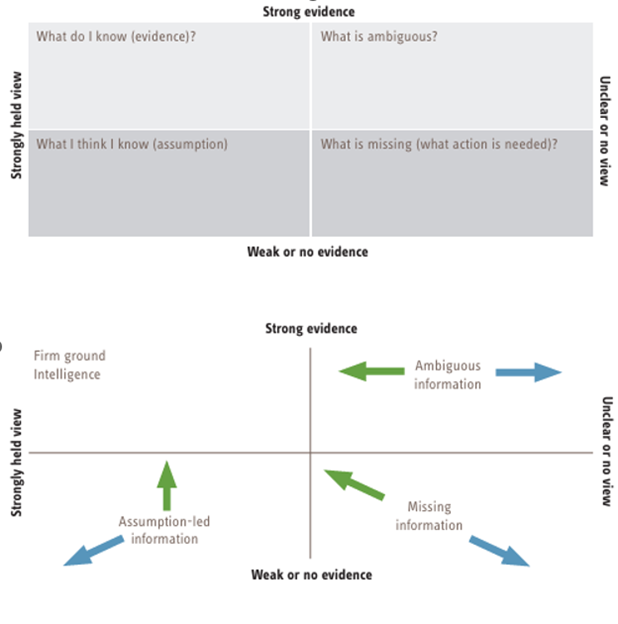

Wonnacott’s Discrepancy Matrix is a reflective tool to help identify and organise information already gathered to support managing uncertainty by enabling more effective analysis.

(Source: Research in Practice)

Often, social care practitioners find allocating time for reflection challenging due to workload responsibilities and deadlines. However, discussions with peers, colleagues from other teams and during supervision provide valuable opportunities for reflection. See Reflective Practice.

Professional curiosity is an essential part of social care and requires you to consider how you engage with the people you are working with. You should show an interest and explore situations rather than making assumptions while being aware of your own values and areas in which you lack confidence.

Verify the information you have gathered, discuss with other professionals and question if you feel there are gaps, or if something is not making sense to you. Be prepared to have difficult conversations and ask relevant questions, focusing on the need, voice and ‘lived experience’ of the person or family.

Pay attention to what is not spoken, what you see, how the person is communicating and explore possible causes, allow yourself to think the unthinkable and believe the unbelievable.

Last Updated: February 10, 2026

v12